Beyond the rubble: learning under fire

By Najwa Sabek | MUBS – Lebanon

In the heart of southern Lebanon, the sound of learning has been silenced by war. The 2023–2024 Israeli aggression displaced over 1.2 million people, destroyed homes and schools, and forced nearly 600,000 students out of the classroom (Save the Children, 2024). When I presented my field research “The Impact of War on Education and Mental Health in Southern Lebanon” at the DSA2025 conference in the UK, I didn’t just share numbers. I shared the lived trauma of a generation under fire.

This blog is a call to development researchers, educators, and policymakers: Lebanon’s education crisis is not peripheral. It is central to the global development agenda.

Above: A damaged school which is now a shelter for the displaced

A nation in perpetual crisis

Long before the recent escalation, Lebanon was already in survival mode. The country had endured:

• A deepening economic collapse

• The 2020 Beirut Port explosion

• The COVID-19 pandemic

• The continued strain of hosting over 1.5 million Syrian refugees

By 2024, more than 600 public schools had been transformed into shelters. In the south, over 70% of schools were completely shut down. Remote learning was not a viable alternative: frequent power outages, bombed infrastructure, and widespread trauma made digital access—and concentration—impossible.

This is no longer just an educational crisis. It is a development emergency with global implications.

Above: Where learning used to take place, children now shelter in the classrooms which host displaced communities.

Methodology: stories from the ground

My research combined quantitative and qualitative tools across 15 public and private schools in conflict-affected border villages. A total of 150 participants—students, teachers, and school leaders contributed to the data.

• Structured questionnaires captured displacement, school attendance, psychological stress, and access to learning.

• Semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders—including the regional governor, Ministry of Social Affairs officials, Lebanese Red Cross representatives, NGO education officers, and school principals and social workers provided deep, human insights.

What the data revealed

• 92.7% of students were displaced

• 80% had their homes damaged by shelling

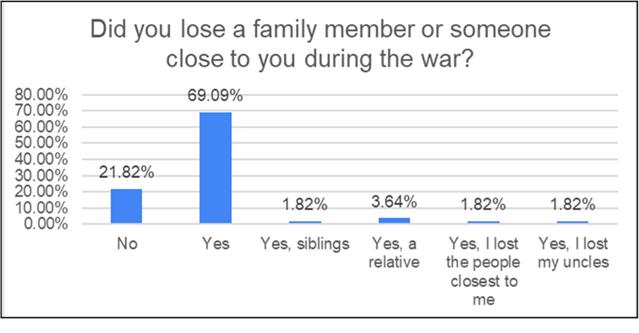

• 78.2% experienced personal loss

• 81% of teachers reported their schools were bombed or directly impacted

But beyond physical destruction, the psychological toll is even more alarming. Children exhibited anxiety, disengagement, and symptoms of depression. Teachers, too, were affected grappling with secondary trauma as they taught amidst ruins and personal loss.

“My village and the surrounding area were bombed. Students lived in constant fear,” shared one teacher. Many schools became shelters, forcing children to learn in cramped, chaotic, and unstable conditions – when learning happened at all.

Community resilience on the ground

In the weakened of a coordinated state response, local resilience emerged. Grassroots initiatives -particularly women-led efforts in Hasbaya and Marjeyoun -distributed hygiene kits, food, and psychosocial support.

Above: The Union of Progressive Women organize to deliver aid

Programs like EKF’s “Lifeline – Hasbaya”, in collaboration with local officials and NGOs, created safe spaces for displaced families,also my university MUBS, The Lebanese Red Cross carried out medical evacuations and aid missions despite dangerous conditions,and NGOs like SHEILD, HUNNA, and the Lebanese Scouts stepped in to provide Social Emotional Learning (SEL) sessions and trauma support to children and women in school-shelters.

These acts of solidarity were powerful but ultimately insufficient. Without long-term institutional support, resilience becomes a temporary patch on a bleeding wound.

Above: BS staff coordinate relief efforts

What development actors must do next

Lebanon’s crisis is not isolated. Conflict zones now account for over 50% of out-of-school children globally (UNESCO, 2022). What’s unfolding in Lebanon is a real-time case study of how war dismantles progress toward Sustainable Development Goal 4 (Quality Education). For development researchers, this moment is pivotal. Lebanon underscores the urgency of:

• Trauma-informed education systems

• Social and emotional learning (SEL) frameworks (CASEL, 2023)

• Community-led educational responses

• Mental health integration into recovery plans

We must ask:

Have these students returned to a state of psychological normalcy?

Are they able to resume their lives as usual?

Are they capable of dreaming again?

Will they trust systems that failed to protect them?

Can future peacebuilding succeed without healing emotional wounds?

What needs to happen next?

To rebuild education in Lebanon, we must prioritize resilience and healing:

• Integrate psychosocial support into national curricula and teacher training (Maslow, 1943; Wallace Foundation, 2023)

• Develop trauma-informed assessments to support diverse learning pathways

• Strengthen digital infrastructure to ensure continuity of learning during crises

• Align policies with INEE Minimum Standards for education in emergencies

Most of all, we need political will and stability. Schools cannot thrive without peace.

From conference halls to crisis zones

Presenting at DSA2025 in Bath wasn’t just a professional milestone- it was a moral obligation. Among some 600 global development experts, I felt a shared responsibility to ensure that Lebanon’s educational collapse does not become a forgotten tragedy.

The stories I carried of students learning through fear, of teachers rebuilding classrooms from rubble, of mothers organizing therapy circles—must echo in development discourse.

To my fellow researchers: Lebanon is not the margin. It is the mirror. Let’s not just study resilience. Let’s fund it, design it, and amplify it together.

Najwa Sabek is a researcher, PhD candidate , senior educator, educational councilor and lecturer at MUBS – Lebanon.

Contact: [email protected] | [email protected] | LinkedIn | Facebook