Why public engagement on aid has never been more critical

At a series of recent webinars hosted by the Development Studies Association development researchers, practitioners, and NGO leaders came together to reflect on the future of aid and the changes to the UK aid landscape. One message rang clear throughout the discussions: if the aid community wants to defend, improve, and future-proof the system, public engagement must be central to that effort. Panellists and participants alike emphasised that without broader public understanding and support, aid remains politically vulnerable and persistently misunderstood.

A shrinking commitment, a growing need

Across OECD countries, aid budgets are shrinking. In the UK, the political climate has led to cuts that were neither widely demanded by the public nor adequately explained. In the Netherlands, although aid cuts had already been signaled in previous years, the formation of a new right-wing government cemented a policy shift: aid would now explicitly serve national interests. Yet, survey data shows that this framing is out of step with public opinion; most people favour aid that supports mutual benefit rather than narrowly defined domestic goals.

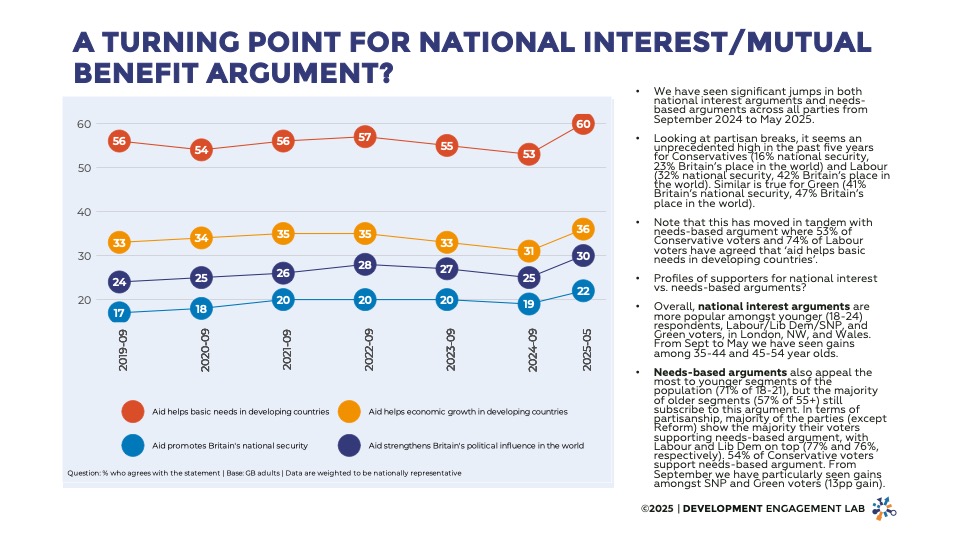

For example: Recent data from DEL’s tracker in Great Britain shows an increase in support for aid that serves both moral and national interests, but the most resonant messages remain moral. The chart below illustrates this trend, with statements like “Helping people in need is the right thing to do” consistently outperforming others. This indicates that while national interest framing has grown slightly, it still plays a secondary role compared to values-based appeals.

Though foreign aid wasn’t a major campaign issue in the US or UK, the cuts were later justified using familiar misconceptions. As Sue Roberts noted in the DSA webinar on reimagining aid, narratives like “we shouldn’t be giving people something for free” played into damaging stereotypes, allowing the public to believe that reducing aid served domestic priorities.

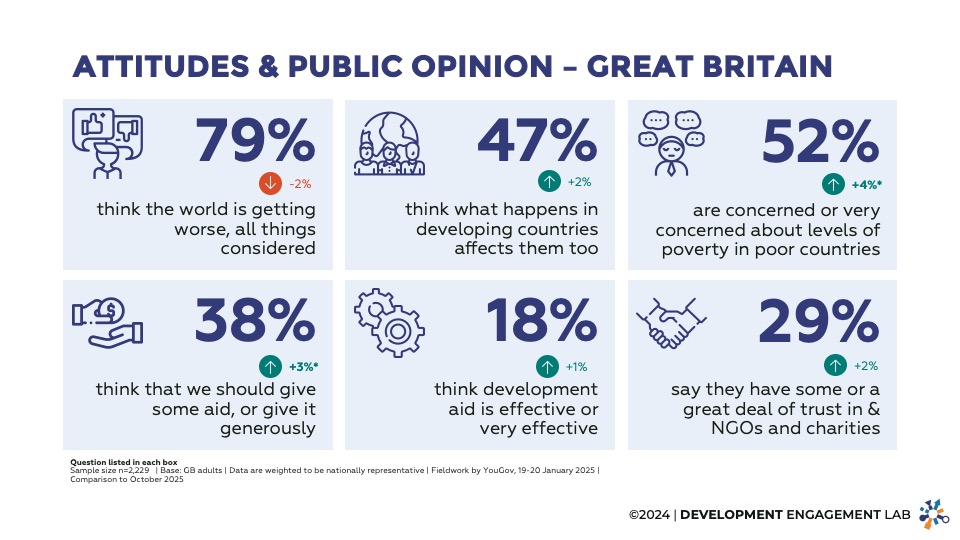

Research shows there is still much work to do on public understanding and attitudes to aid. Perceptions of waste and corruption remain high.

Nicola Banks said during the same webinar that we can’t think about making improvements without engaging beyond our sector. “The public are part of the solution to reimagining a better, values-based aid system,” she emphasised.

The role of DEL: evidence for engagement

This is where the Development Engagement Lab comes in. DEL brings together academics and aid practitioners to build an evidence base for more effective public engagement. It is a space to share insights, test messages, and design campaigns rooted in what works. DEL’s Dashboards also track public behaviour and engagement related to global poverty and overseas aid in Great Britain, France, Germany, the United States, among other countries.

At a time when public attitudes are increasingly shaped by misinformation and partisan narratives, DEL provides a rare, data-driven approach to understanding what resonates and what doesn’t.

Building on this evidence, DEL research shows that statistics alone won’t build public support for aid. DEL recently demonstrated that the lack of compelling aid stories in the media is a barrier to public concern. When those stories do reach the public—particularly around meeting basic needs like food, sanitation, and healthcare, people *do* care. It’s not that the public is disinterested; it’s that stories of aid’s impact have failed to cut through a spiraling news cycle, made worse by outdated but stubborn public perceptions of how aid works.

That said, DEL data show clear trends around what works when communicating aid to the public. Overwhelmingly, in all countries DEL surveys, aid arguments that are based in morality are the most effective. Favourites include, ‘Helping people in need is the right thing to do’ and ‘Every person in the world should be treated equally.’ While recent data (shown above) shows an uptick in the popularity of both arguments for aid that serve the national interest and arguments that serve both moral and national interests, purely moral arguments are still far and away the winners (shown below).

Support for different types of aid messages across countries. Moral arguments consistently outperform national interest-based messages.

Better questions, better conversations

Speaking at DSA’s event on UK aid, Romilly Greenhill, CEO of Bond, highlighted the importance of how we frame questions when assessing public attitudes. “There is a difference between asking someone ‘Do you like aid?’ and asking if they would rather have the money spent on the NHS,” she explained.

She added that more sophisticated messaging — for example, talking about aid as an investment in poverty reduction or gender equality — tends to align better with the public’s values. Insights from DEL can support communicators to segment audiences, tailor messages, and reinforce the kind of framing that resonates.

Reimagining the campaign for aid

Telling better stories is central but so is deciding who gets to tell them. As Russ Hargrave of Politico noted, “Large fundraising charities may excel at mobilising donations, but they’re not always the best messengers when it comes to nuanced political communication.”

Any long-term campaign to revitalise aid must involve communicators, researchers, and journalists working collaboratively to pitch stories that engage the media. DEL data shows that messengers matter: The best messengers for aid are the ones doing the work, namely those in affected communities.

Making public engagement strategic, not optional

If the aid community wants to shape the future – not just react to it – public engagement must be treated as a strategic priority. The stories we tell, the messengers we choose, and the evidence we use will determine whether aid continues to be sidelined or is reclaimed as a powerful tool for global justice.

Find out more about the Development Engagement Lab and how it can help, including access to DEL’s raw data, visit their website or contact [email protected].

You can also watch the DSA webinars on re-imagining a better aid system and what next for UK aid.